Loneliness has always been a part of being human. One can find joy and calmness in solitude, yet pain and emptiness inside our soul follow us through our path of life. That’s why, in my opinion, the idea of ‘God’ is popular and believed rigorously despite changes in culture and time. Because people who are at their lowest point and have no one else to share their pains with have the comfort of gods to pray to and live with a sense of hope.

There are many ways for people to find solace in life, and one of them is through cinema. Cinema is a medium for people to tell their stories, which lets them converse with and feel affected by what’s on screen. After it ends, it leaves you with something, and it’s sometimes even capable of changing a person.

Both God and cinema are always there for people. In this article, I will look at how cinema has depicted loneliness through various films as examples.

Wild Strawberries (1957)

Bergman’s Wild Strawberries follows Isak Borg, an old doctor who’s still nostalgic about his childhood and feels guilty about the way he led his life afterward. He goes through a journey where he meets strangers and familiar faces, but the world is a different place now for him, which makes him feel detached from them. Between remorse, solitude, and fear of death, he finds solace in his memories of childhood. This journey of his character makes for a powerful tale on aging, loneliness, death, and being a better person.

Her (2013)

In Her, Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) befriends an AI chatbot, Samantha. But things take a huge turn when he falls in love with her. She’s the only one who’s there for him every day. Even in a futuristic world where technology becomes so much advanced, people like Theodore are still longing for human connection. Spike Jonze’s Her makes us see many complicated relationships. It is a poignant exploration of loneliness and relationships.

Ikiru (1952)

Ikiru is about an old bureaucrat, Kenji Watanabe, who feels left alone by the world and family. He is almost a walking ghost. But fate changes him. Upon finding that his own family members view him as an annoyance, he sets out on a journey. He pursues pleasures through bars and friends. It’s not long before this escapade makes him realize the purpose of his life. Kurosawa’s heroic portrayal of him in the third act is absolutely phenomenal, which ends with a strong message for the audience to do something for society. When Kurosawa’s films have a ‘message’ to the audience, it doesn’t feel like advice but a warning. It’s one of the very rare hopeful films you’ll find in this list.

Nights of Cabiria (1957)

An honest portrait of yearning with the help of Giulietta Masina’s great performance as Cabiria. Cabiria yearns for respect and love. But sadly, her life offers her tragedy after tragedy. Fellini’s films are a product of a colorful world filled with caricatures and odd Italian sense of humor, but his main characters are left alone, unaware of how to go on with their own lives. It’s a mystery that disturbs so many people like them and drives people like Cabiria to solitude.

Vivre Sa Vie (1962)

Vivre Sa Vie is such a sublime work of art. Godard’s brilliance is visible in every scene. Anna Karina plays a tragic character who’s quite similar to Cabiria. The scene where Anna Karina’s character cries while watching The Passion of Joan of Arc is so pure and captivating. It has an arresting allure to it which makes the audience realize what they’re watching is something special. Vivre Sa Vie is indeed a special film.

Blow-Up (1966)

Antonioni’s character study of Thomas, who exploits people who come to him for photoshoots, takes a big turn when Thomas witnesses a murder and photographs it. Thomas feels lost in this web of finding out about the crime. His character feels emptiness and wanders around places, but this crime enters his life and gives him a purpose. The whole crime subplot in Blow-Up is so mysterious and vague to follow for both Thomas and the audience. At the end, everything loses clarity. It influenced a couple of classics like Coppola’s The Conversation and De Palma’s Blow Out, where its protagonists fall into the web of crime, affecting them personally.

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Brussels (1975)

Chantal Akerman’s excellent film portrays Jeanne Dielman’s daily monotonous lifestyle as a housewife. She goes through a lot to raise her son. Akerman’s minimalistic approach makes it feel like a horror film, where the sound design plays a huge part in the film’s greatness, making the small things much bigger in context. It’s a horrifying outlook on life. It made a lot of noise when it topped Sight & Sound’s best films of all time list. I am one of those people who believe that this film deserves that praise.

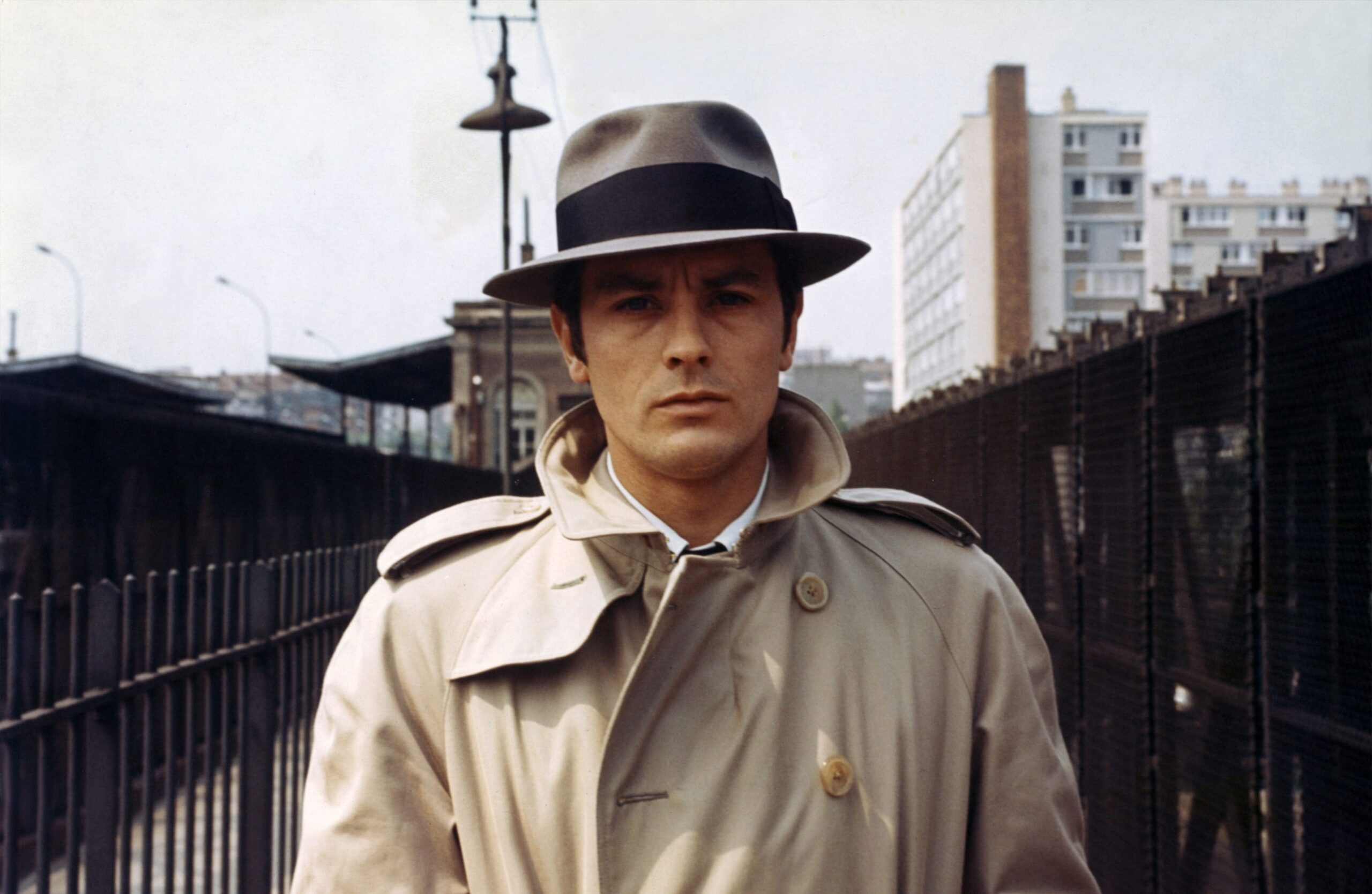

Le Samouraï (1967)

One of the very first films to portray a lonely character as a cool, macho hero. It’s significantly because the lead character, Costello, is played by the popular actor Alain Delon, and the way Melville’s camera captures him. Costello is a lone assassin and has a certain code to his job. His life falls apart in a crisis. He has a small bird as a pet, but other than that, he’s a lost soul and barely talks. So much so that it feels like a joke when the police put a bug in his house. That’s why Costello’s world changes altogether when he finds a companion. It’s such an influential film on John Woo, where Chow Yun-fat is his lonely cool macho hero akin to Delon in films like The Killer (1989). It echoes in Michael Mann’s works too, like Heat (1995) and Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999). Like these films, Le Samouraï’s influences are numerous, and it still remains an iconic film.

Days of Being Wild (1990)

“I’ve heard that there’s a kind of bird without legs that can only fly and fly, and sleep in the wind when it is tired. The bird only lands once in its life… that’s when it dies.”

In Wong Kar Wai’s world, lonely characters swarm in and out of Hong Kong, which has its own characteristic. Several people remark that there’s always too early or too late for lovers in Wong’s films. Two characters meeting in the right time, which is a magic moment, happens rarely in Wong’s world. They always fall in love, but time and situations scar their relationship.

I don’t want to reveal whether that magic moment happens or not in Days of Being Wild. There are multiple characters who fall in love and become embroiled in its world of solitude and pain.

They’re all deeply saddened by life and become like a wandering bird in a neon city. It is a great film filled with a lot of powerful little moments between the characters. Small moments matter the most here. Wong depicts his characters’ loneliness and relates it to the loneliness of the whole world.

Pickpocket (1959)

In Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket, the main character Michel is a lone soul. Despite having friends, he doesn’t feel attached to them, as he has his own problems to look out for in his life, which he doesn’t want to share with anybody. It is inspired by Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. The cast are not trained actors, as Bresson’s films function in a different way. The gestures and looks are very important in a Bresson film because of his minimalistic approach to filmmaking. In Pickpocket, the shots of hands are so evocatively filmed, whether it is for showing the act of theft or love. It’s an important film that influenced many artists, especially Paul Schrader, whose films we’re going to discuss next.

Light Sleeper (1992)

Paul Schrader, both as a writer and director, has a great number of films that focus on lonely characters inspired by Pickpocket. This follows the template of Taxi Driver, and at the same time, it manages to bring forth many different elements in its story. Willem Dafoe stars as John LeTour, and it’s one of his great performances. Even though the typical protagonists of Schrader’s work always end up doing something that helps the person they adore at the end, there’s a sense of selfishness hidden in their actions. By doing something good, they satisfy their own ethical egoism so that they can create an illusion where they can remember themselves as the person they always wanted to be.

It is different in this film. There’s no cynicism hidden in the main character’s actions in Light Sleeper. It might be Schrader’s most humane work. Paul Schrader even calls this film his most personal work in 2005. First Reformed, a much better film from Schrader, might have taken that place as of now. Even though they all follow a character who has a habit of writing a diary, has developed a sickness to their surroundings, and a desire to change the world they live in, and importantly, is very alone, Schrader’s work is unique in its own way. And Light Sleeper is one of his most interesting films.

Taxi Driver (1976) & The Searchers (1956)

Paul Schrader’s Taxi Driver script fell into the hands of Brian De Palma, who persuaded Scorsese to direct it. When Scorsese read the script, it reminded him of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. He wanted to film it in a way that was unlike anything else. Dostoevsky’s book provides a fascinating depiction of a lonely character, and reading it feels like hearing the ramblings of a stranger nearby. This deep human depiction is reflected in Taxi Driver.

The 70s were a transformative time in cinema. For the audience, Travis Bickle is no stranger. Many films from that era feature vigilante characters, like Death Wish. However, what sets Travis apart is the realistic portrayal of his life and New York City. Scorsese’s unique approach to filming Taxi Driver immerses you in Travis’s world while simultaneously disorienting you. For example, there’s a powerful scene where Travis calls Betsy but receives no answer. The camera pulls away from him to show an empty space leading to the door. We’re left to wonder if something will happen, but nothing does. This absence reflects Travis’s profound pain, keeping the audience in his torment.

Similarly, the 50s were a revolutionary decade for cinema, marked by John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). The Western genre was popular, and John Wayne was the quintessential ‘cowboy’ figure. However, Ethan Edwards in The Searchers feels different. Ford captures the essence of community and family in his films. When Ethan, a product of a different world, intrudes into a caring family’s life, their world shatters. He still harbors hatred from the Civil War, which he directs at Native Americans. Both Travis and Ethan exhibit racism, believing their worlds have lost their purity and acting out accordingly.

Racism is more direct in The Searchers. Native Americans were often depicted as forces of evil in Ford’s films and those of his era. Ford’s perspective shifted in the late 40s with Fort Apache, and he directed Cheyenne Autumn as an apology to Native Americans for his previous films’ treatment of them. Characters like Ethan and John Wayne still carry that hatred, and they are resistant to change. The excellent finale of The Searchers shows Ethan bidding farewell, symbolizing a departure for people like him. This iconic shot of John Wayne’s anti-hero Ethan exiting through the door signifies that the world does not need vigilantes like Travis and Ethan. They are left alone, no longer disturbing the normalcy of the world that created them.

Chaitanya Tuteja is someone who enjoys sharing his thoughts on books, movies, and shows. Based in India, he appreciates exploring different stories and offering honest reflections. When not reflecting on his favorite media, Chaitanya enjoys discovering new ideas and embracing life’s simple moments.