Paul Thomas Anderson is special. He’s been stunning us with his intimate, yet brutal depictions of complicated, dense, and memorable characters for the last 30 years. He’s a unique voice and a standout compared even to his greatest contemporaries. Though the question lies… has he become too good?

The Energy Shifts of PTA’s Career

PTA has a very distinct energy, which has mellowed and accelerated at different points during his career. Though each film’s energy is dictated by the character. Every film in PTA’s filmography has a particular emphasis on ‘character’, in early films, his characters weave in and out of each other, cross paths, and are connected by varying thick and thin threads. In his later career, the characters become more solitary, lonely, and driven by questionable moral codes. There is a clear distinction between these two periods, the first half lasting from 1996 with his debut ‘Hard Eight’ also known as Sydney to 2002, with his Adam Sandler starring “Punch Drunk Love”. This era we can define as ‘Coke PTA’ (due to his fondness of the drug), and the other half which we can dub ‘weed PTA’ starting from There Will be Blood in 2007 until 2017 with Phantom Thread.

The “Coke PTA” Era

Anderson’s career is dense. So it’s impossible to talk about every film in excruciating detail, so we will begin with the first half, the Coke PTA. This period can be noted by a heavy influence from Robert Altman, with large, star-studded casts, and complex interweaving stories. The films are ambitious and soar through runtimes up to 3 hours in the case of Magnolia, with a great amount of kinetic energy. Despite the sweeping stories of Magnolia and Boogie Nights in particular, what really gives the film soul, and what makes PTA’s unique voice stand out are the characters.

A Recurring Theme of Searching for Connection

PTA’s characters are flawed and they yearn for a connection, this begins from his very first film Hard Eight, the emotion, the driving force of the entire film is built from the father-son connection between John C Reiley’s John and Phillip Baker Hall’s Sydney. It deepens with the romantic subplot with Gwyneth Paltrow’s Clementine. This theme continues again and again, a character is searching for a connection, a bond with another, be it a father figure e.g. Sydney for John in Hard Eight or Jack and Dirk in Boogie Nights, or something romantic like Claudia and Jim in Magnolia. All of this comes to a head in Punch-Drunk Love.

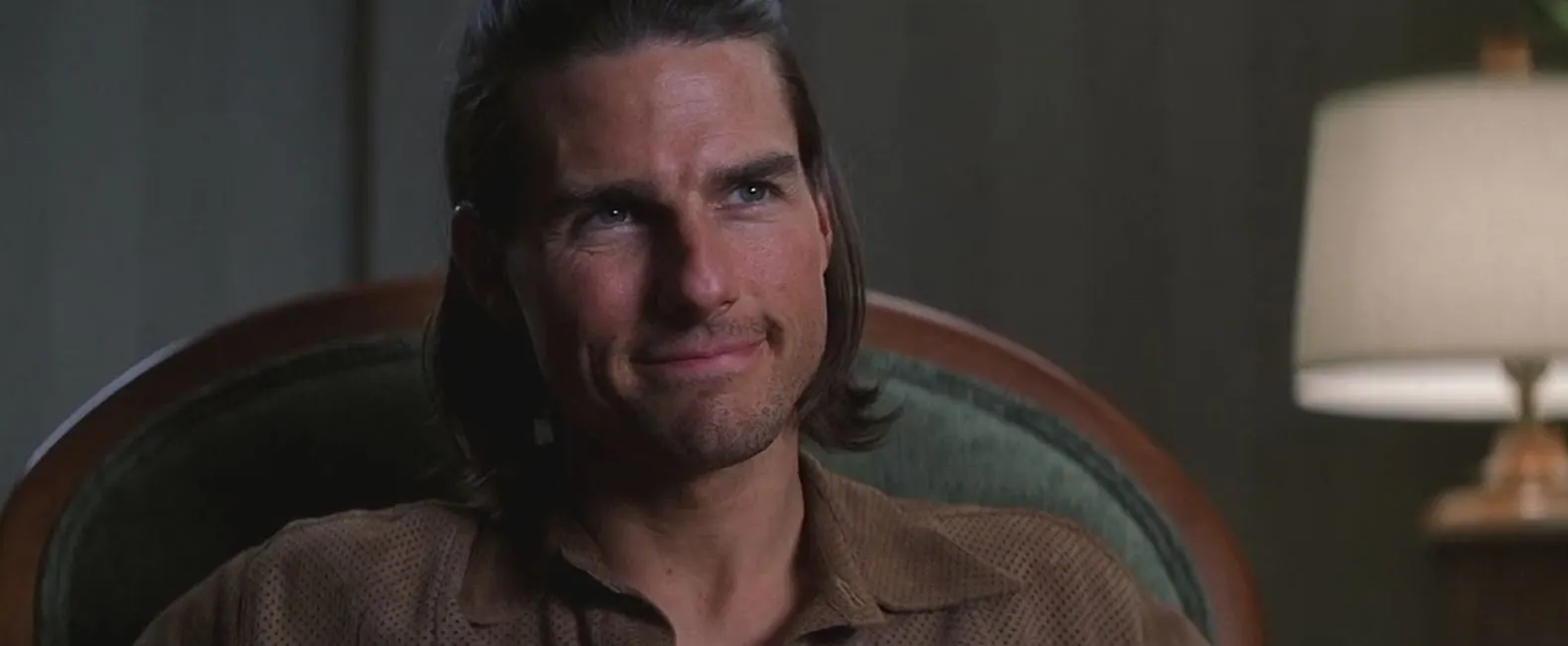

Punch-Drunk Love as a Turning Point in PTA’s Career

Punch-Drunk is more isolated, it focuses on one character in particular, rather than a wide range of eclectic personalities. It hones in on Adam Sandler’s Barry Egan, a quirky, autistic man who struggles to find solace in his romantic and familial connections and is bullied by his sisters and undermined by most due to his perceived weakness. This sounds very different from the films mentioned previously, yet it falls under the same bracket… This is due to the energy the film exudes, it moves, and it bounces, Barry is a character seemingly always on the run, on the move, overwhelmed.

We are put into Barry’s shoes, primarily through the soundscape, sound effects are heightened and we are overwhelmed by quite a dominating score written by Jon Brion, that includes enough bounce and funk to emulate the idiosyncrasies of Barry. This move into a sole character focus is a step towards what we would frequently see from PTA in the future. Punch Drunk Love is his shortest film, the smallest in appearance, and doesn’t seem as ambitious as his other works before or since.

Yet it remains potentially the most important and the greatest signifier in the change of PTA, he was never the same since… Punch Drunk Love gave us a quiet call that change was coming, and laid a foundation for the future of character-focused film from Anderson.

A Return to Childhood with “Licorice Pizza”

Before moving on to the second period of Paul Thomas Anderson’s career, it’s important to talk about his most recent film to be released at the time of writing- Licorice Pizza. Moving away from mature, slow-paced, quite distinctly ‘adult’ films, PTA taps back into his childhood and moves back towards what began his career. Licorice Pizza dollies with more speed, it moves quicker and the characters flow and sprawl through the San Fernando Valley pulling away and back closer again to each other like a rubber band. The themes of connection remain, but the energy returns to a kineticism that seems missing from There Will Be Blood until Phantom Thread. Could this be the next signifier of change in PTA’s career? Might we see another switch in style in his upcoming film The Battle of Baktan Cross? Time will only tell, but with the early word on the street being that this could be PTAs most commercially viable film he’s ever made, is quite a strong sign that we could be in the emergence of another arc of Paul Thomas Anderson.

The Shift to “Weed PTA”

After Punch Drunk Love Anderson really nailed down on one character. Putting all his focus on a singular psyche, and breaking it down to its smallest parts. There Will Be Blood, commonly thought to be his magnum opus, is a cold, dark, brooding film. Gone is the energy of Robert Altman, now we have the sinister mood of Stanley Kubrick. Shot with greater restraint, distanced from the audience, and requiring patience and mindfulness to really get beneath the skin, and to unravel the subtleties within.

The ambition remains, it’s a leap in another direction and retains the scope and scale of his previous films, but is seemingly more focused. One thread connects this period to the previous, and that is his common theme of connection. Daniel Plainview is a man who uses and abuses those around him to gain power. There Will Be Blood is a destruction of greed and the American Dream. Plainview navigates his connection to the townspeople, the church, and his son, all linking back to his own personal drive for greed.

Before PTA would focus on his characters yearning to connect to others, now Daniel Plainview only yearns to connect with profit. Business and ego are the only things that drive him, his competitive spirit becomes all, and any opposition is a threat, he is there to destroy, at any length. Empathy and emotion are weaknesses, down to the tee of his own son. A complete departure from the nurture and love we would see before, Anderson has become cold, and pessimistic, though not heartless.

Coldness and Isolation in the “Weed PTA” Era

Anderson at this stage in his career is focused on solitude and the harm of closeness to others. The Master, in what seems to be a comfortable, homely solace for Joaquin Phoenix’s character Freddie Quell under the roof of Lancaster Dodds’s religion. The further Freddie gets drawn into this religion and the closer he gets to Lancaster, who acts as a foster father to Freddie, the more the cracks begin to show. The same happens in Phantom Thread, where Reynolds can only handle one figure of authority in his life, and when this is challenged, his coldness is broken, and he opens himself up to another woman, Alma, he cracks and his life appears to fall apart.

Distance and coldheartedness come with acceptance, in The Master, it’s about letting go and returning to be a free spirit, in Phantom Thread, it’s about embracing, and accepting a new way of life. Though twisted, the mutual agreement of power between Alma and Reynolds is mutually beneficial, they both agree to take turns being above and below each other, Reynolds even accepts being poisoned in order to be mothered. Though this may argue that Anderson portrays closeness as a toxin, something that causes harm and should be released, distance is good for the driven man.

Daniel Plainview achieves success, but he is living in a desolate mansion, standing only on wealth. Reynolds is only allowed to continue progress in his life after being periodically poisoned. Anderson captures this with fragility and beauty, but this could be a mask for a much more pessimistic outlook than you might hope

The Inimitable Auteur Paul Thomas Anderson

Paul Thomas Anderson is inimitable. He built upon his influences, using his incredible knowledge of cinema to his advantage, allowing him to remain within the rules and confines of what is considered ‘usual’ for cinema, but being alien enough to subvert where he can. This puts him in a unique position of having almost free reign over the characters he chooses to portray. In an ever-changing industry, it’s hard to imagine future clones of PTA coming forward out of film school as we often do nowadays with endless imitations of Edgar Wright and Quentin Tarantino hitting the shelves by the truckload.

PTA has become so distinguished in his revels of the human condition that it seems impossible to replicate. His writing is so dense and rife with hidden character, and his style is just so slightly off-balance, that it’s immune to imitation. You can make comparisons to the past, as I have with Altman and Kubrick, but even then he has progressed and made himself different.

He hasn’t done the genre work of Kubrick, and he moved away from the ensembles of Altman, he has defined himself as his own man. His own auteur. And as somebody with such a strong sense of self and such a passion to do exactly how he deems fit, from such an early age, it almost seems a sin to try and replicate him. I doubt we will see Anderson make particular waves on future filmmakers in trying to replicate his style, but instead, he will be used purely as a figure, somebody to look up to, not a god, but a goal.

Chaitanya Tuteja is someone who enjoys sharing his thoughts on books, movies, and shows. Based in India, he appreciates exploring different stories and offering honest reflections. When not reflecting on his favorite media, Chaitanya enjoys discovering new ideas and embracing life’s simple moments.